"As Ghana celebrates its 50th year of independence from British occupation it is closely watched by the world as an example of West African prosperity. It has had the most stable economy and political history of any of the West African countries and as the first nation to achieve independence from British colonialism in the region, is a shining example to the world. However, it has by no means had an easy ride, the first President, Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown several years later in 1966 in a coup by the army and over the next fifteen years several presidents came and went as corruption and coups became ever more rife. Eventually Flight Lt JJ Rawlings took the reigns in 1981 and was the countries president until a few years ago. During his time in office he imposed a strict regime on the Ghanaian public and often opposition to his party would quietly disappear. Now things are looking up and there is a much more healthy democratic process in Ghana. However, the economy is still experiencing troubles as it struggles with inflation which can be seen in the ridiculous amount of notes required to pay with. At roughly 18000 cedis to the pound and the largest notes being 20000 it took quite some time to pay a three hundred pound hotel bill at five in the morning. It also is the main base for UN peacekeeping in the area and as such has strains put on it helping to accommodate this.

Arriving in Ghana it is immediately evident that the country is still developing. There are few buildings over two storeys and those with a consistent supply of electricity and water tend to be hotels and the Kofi Anan UN training facility. Many live down dusty, unpaved streets in small corrugated iron roofed huts or part finished concrete buildings. Large areas are subject to random blackouts through the night due to energy shortages and in recent years water has been the same. The weather is hot and humid, around 30 degrees Celsius, as the rainy season approaches.

After a day to acclimatise and visit the local sites it was a 5:30am start to catch the bus up to Tamale, the capital of the Northern region of Ghana. Symptomatic of life in Ghana the bus was three hours late departing but Alan and I were soon wedged uncomfortably in for the fifteen-hour journey ahead. Along the way overturned lorries regularly littered the sides of the road, their goods spilled across the tarmac. Held up at these intervals we were soon provided all forms of strange plant and wildlife from the street hawkers. They were selling any thing from bananas to giant land snails, a delicacy when cooked in a stew. As the women in front of us picked eight of the juciest snails into a black plastic bag, Alan and I wondered where she would keep them for the nine hours we still had left to travel. Eventually we reached Tamale station at 2 in the morning where our guides met us.

The next day we proceeded to the village Gurugu, which is local to Tamale. It is here that the main body of the cooperative operates producing Shea Butter from the Shea nuts bought locally. The village houses roughly 5000 people and the co-op have roughly 120 women working for it. Some are from the village and others are from another local cooperative who have joined to increase production. Work is by demand and varies as orders are placed. The village itself is made up of basic mud huts, which cost around £150 - £200, to build. Although primitive looking the houses withstand strong winds and rains during the rainy season. Standing on the dusty road the site of production is a collection of these rudimentary buildings, their straw roofs tightly bound, and a large sheltered concrete platform which has been recently built with the help of a local NGO group, led by a WTO initiative to encourage industry.

As Alan and I arrived we were at once welcomed with approximately thirty women all dressed in large, brightly patterned dresses and equally garish headscarves. Some have tribal scars on their cheeks others tattoos. Launching enthusiastically into song the women dance for us in a line, as an official village welcome finishing with a loud kiss noise which we all find funny. After this we are introduced to the various women leaders of the group all of who look like strong minded matriarchs and remind me of old schoolmistresses. We hear a brief history of the groups and how their work practises have been much improved since NGO training in November enabled them to reach commercial grade Shea Butter.

Then we are able to walk round the small ‘factory’ all of which is open air. Immediately in front is a large pile of Shea nuts surrounded by a crowd of women all bent over the pile removing the poor quality black nuts from the brown, something they are less inclined to do when paid standard local wages. From here the nuts are taken to be crushed in a grinder, a new addition to the facility as this used be done by hand. At the far right is the roasting area where small open fires roast the crushed nuts to soften them for blending. Here several large blackened cylinders house between 50 to 80 kg of nuts. They are spun continuously over the intense heat to prevent burning for around 45 minutes. As Alan experienced, this is hard work, smoke blowing in to his eyes, he lasted about 4 minutes before giving in to the heat.

Then two women will lift the heavy vessel and move it back to the concrete platform where its placed in a large aluminium bowl to be beaten by hand with a mixture of water to separate the butter from the other materials. Under the iron roof sit several women, there legs aside the bowls and there fists balls of brown Shea mix as they beat the Shea whilst occasionally breast feeding one of several small children strewn about.

Alan and myself can say that it wasn’t as easy as it looked having to beat the mix until it became a smooth blend. As we both tried to master the art the women laughed raucously and pointed as sweat dripped from our noses, in the end we left, defeated, not even having produced one bowl of butter between us. Next the mix is washed a total of six times to separate impurities and the material begins to resemble the yellow/white material that will be carefully wrapped and sealed in a small building across the yard.

The entire process is manual and extremely hard work where the women are expected to lift heavy bags of 50kg or more and work through the day to produce the orders. They can make up to 900kg of Shea butter a day and were processing our order whilst we were there. The men of the village will not work and take casual labour in building huts and maintenance as and when. The tradition is for the women to bear the brunt of most of the work within the village. All though an intensive workload there was much laughter and sense of community here mixed with the hardy living conditions.

The next day Alan and I felt relaxed, following the formalities of the previous morning, songs and sit downs with the women out of the way we looked forward to stress free day. However, when our unexpected meeting with the chief was moved forward an eerie tension fell over our guides and the friendly faces of the village became wracked with worry. We were told that the chief and elders of the community would be presented with a gift of soft drinks from us and we must be gracious in accepting thanks. Alan and I exchanged disconcerted glances as a line of wizened old men, some clutching knarled canes, others missing teeth or with cataracts on their eyes, filed into a slightly larger mud hut. Following them some of the women leaders from the group and then us.

Nervously we sat on a creaking bench the stifling heat inside equalling the tense atmosphere. Sweat trickling down our backs, we were sat to the left of the circular ‘Palace’ and were facing the cross-legged elders. cold eyes staring out the gloom of the large hut. On our left, lounging on the raised platform in his throne was the Chief of the village. A heavy silence settled on the group and my heart began pounding in my throat. Suddenly I was wondering whose idea this was, maybe I could go and wait outside whilst Alan negotiated, at least one of us could report home on what had happened…

The leader of the womens group, Madame Jerang, slipped from her position on the bench to crouch on her knees and addressed the room. Ensuring she was suitably lower in stature than the Chief, she explained our business and what we were planning to do in supporting the village. Soon she asked if we had anything to add and I could feel beads of sweat dripping into my eyes. Quickly prompted I blurted out something about a “wonderful welcome” and “great working relationship for the future”. After this the soft drinks were served and we all breathed a sigh of relief as the atmosphere broke and smiles and cola began to circulate.

Looking round the palace there were a list of names in chalk on the wall. Each name was one of the chief’s children. Carefully counting up we could see that the chief had approximately twenty-six children with his three current wives. It was no surprise that he sat staring vacantly into space whilst members of his ‘board’ spoke for him. He must have been exhausted.

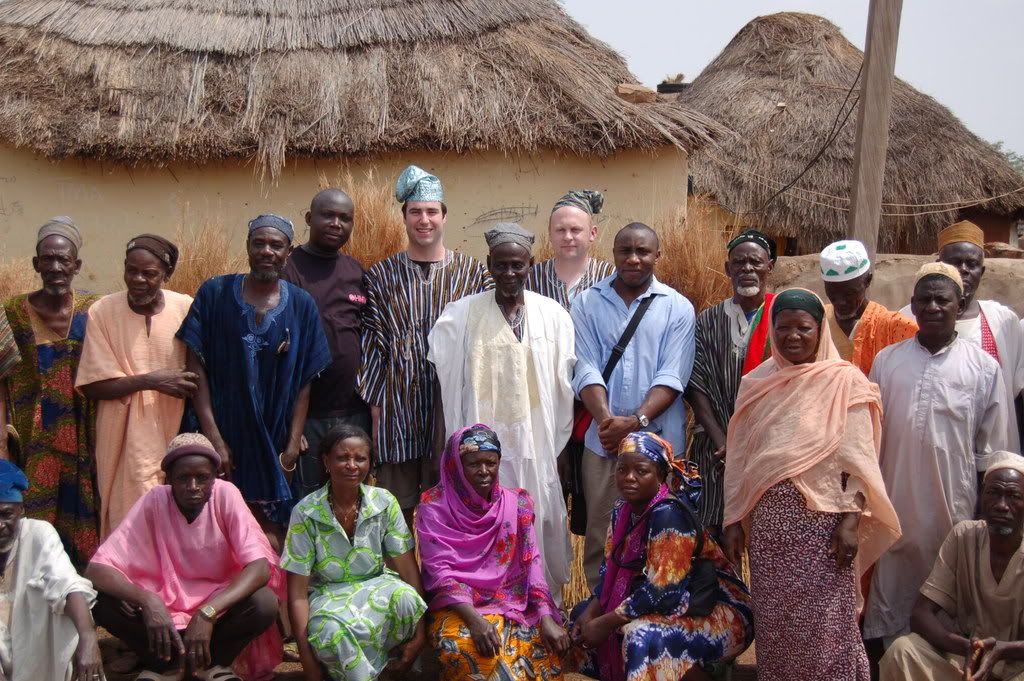

Expecting the worst was over Alan and I thought we were home free. Then they decided to present us with gifts. In true Gurungu fashion Alan stood up and was presented with traditional robes and funny hat. Convinced they had chosen the most ridiculous hat in the world for Alan, I roared with laughter until I spotted the sparkly green one they had for me. Stepping out into the hot sun wearing striped heavy tunic and glistening hats we stood with the Chief for photos. The entire event was very formal and steeped in traditions and codes of conduct, but we made it through and felt like we really had met the people we were dealing with.

After the tension of the morning passed we were taken to the Shea markets in a neighbouring village. Along the way the area was strewn with wild growing Shea trees. When the Shea fruit is ripe locals will pour into the area to harvest it. Competing with hungry snakes the process is often treacherous. The area is relatively un-cultivated with some rudimentary fields ploughed round the tress to grow yams and other local foods. No pesticides are used in the area as they are too expensive and are not warranted for the production here so the fruit is naturally organic. Recently mango plantations have sprung up and are threatening to turn local land to mass production of mango in the future. However, this is some way off for the time being and Shea trees can be seen growing far over the horizon for much of the journey to the markets.

Unfortunately there was no activity at the markets but the large empty stalls lining the dusty square of the village gave a good impression of the scale of the event. Here the nuts are brought from the surrounding area to be traded by the local processors. The women from the co-op will come here to buy up their quantities of nuts once we have placed our orders. To initiate this process we have agreed to pay 30% of the cost of the Shea upfront for each order.

Attracting more and more attention from the local school children we were soon amongst a throng of chattering kids. They took us to meet another local elder and we were granted permission to pick a baobab fruit from an eerie looking local tree. The fruit was a large dry cocoon, which was split open to reveal a powdery white substance tasting of sherbet. Apparently if you eat too much it can make you run to the toilet so we didn’t tell Alan and watched him take hearty mouthfuls of it whilst the congregation of school children giggled.

Soon it was the end of another busy day and one that both Alan and I will always remember.

Travelling to Ghana was a real eye opener. Images of Africa and its poverty are common in the UK, but to see a relatively prosperous country still have the majority of its inhabitants living in mud huts, burning timber as there primary energy source and living in tribal communities where its common to have several wives and eight or nine children was still shocking. It is easy to see how open to exploitation and corruption the area is and indeed this is a big problem for the local people. I felt that our support of the Shea project was one that was sustainable and benefited both sides, using a traditional local commodity and creating prosperity from trade with Lush. It is important to realise that we have entered into a longer-term commitment where we can build a relationship with these people and both profit from the business. We found everyone we met friendly and open who made us feel very much at home."